-

Early indigenous people transform coal found in seams in foothills and mountain regions into effigies.

Most of the effigies depict bison, usually cows, with tongues out, indicating either running or being in labour. The specimens have all suffered damage from ploughing but are still remarkable and accurate anatomical reproductions of bison.

Source: Royal Alberta Museum

-

The presence of coal in Alberta is first recorded by a European explorer.

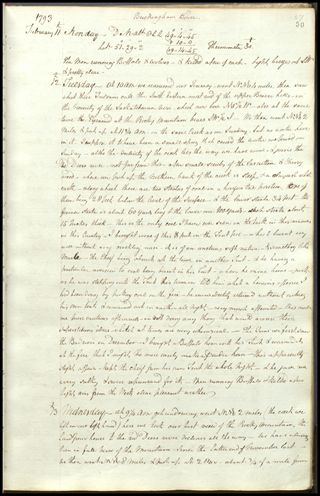

In the February 12, 1793, entry of “Journal of a Journey over Land from Buckingham House to the Rocky Mountains in 1792 & 3 by Peter Fidler,” Fidler describes his coal discovery.

Source: Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Archives of Manitoba, E.3-2 fo.30

-

The first commercial coal mine begins operation in Alberta.

Nicholas Sheran’s mine, 1881

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-1948-2

-

The first large-scale commercial mine begins production in Alberta.

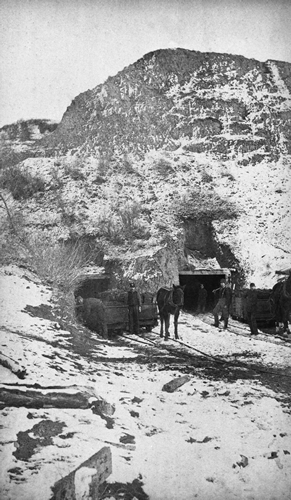

The entrance to Galt Drift Mine No. 1 in 1885 near present-day Lethbridge; Sir Alexander Galt establishes the mine to exploit the region’s abundant coal deposits. Galt also establishes the North Western Coal and Navigation Company in the same year to supply coal to the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-3188-43

-

Coalmining begins in the Crowsnest Pass region of Alberta.

A view of International Coal and Coke Company at Coleman in the Crowsnest Pass, ca. 1912, eleven years after production started; the region yields a high volume of industrial steam coal.

Source: Image courtesy of Peel’s Prairie Provinces, a digital initiative of the University of Alberta Libraries, PC003325

-

The Coal Branch mines open southwest of Edson, Alberta, in the Foothills region.

Early Brazeau Collieries at Nordegg, Alberta, in the Coal Branch mining region, ca. 1913; German immigrant and entrepreneur, Martin Nordegg, establishes the mine operation, which leads to the founding of the Town of Nordegg in 1914.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-4093-52

-

First large commercial mine in Drumheller Valley starts production.

Horses pull coal-filled wooden mine cars underground at Newcastle Mine in 1914, three years after Newcastle opened in Drumheller Valley.

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, A6152

-

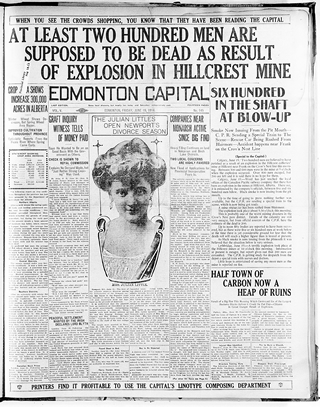

Alberta’s deadliest coalmine disaster occurs at Hillcrest, Alberta.

An initial gas explosion triggers a larger coal dust explosion, killing 189 miners. The initial fatalities estimate reported in the Edmonton Capital newspaper on June 19, 1914, was later revised.

Source: Image courtesy of Peel’s Prairie Provinces, a digital initiative of the University of Alberta Libraries, Ar00113

-

Cost of living rises by 65% since onset of World War I in 1914, contributing to coal industry labour unrest and heightened union activity.

Strikers from One Big Union (OBU) at Drumheller, Alberta, in 1919; the union forms after labour workers broke away from the United Mine Workers Association union. Miners are drawn to OBU because of their deepening economic crisis.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-2513-1

-

The province is divided into thirty-two coalmining districts as the industry expands broadly.

Newcastle Mine in the Drumheller mining district of the province after ten years of expansion in 1921; Drumheller is one of thirty-two districts created to facilitate keeping track of the booming industry’s developments, inspections and infrastructure requirements.

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, A6081

-

The Second World War begins to revive Alberta’s economy and coal industry, which had declined during the Great Depression.

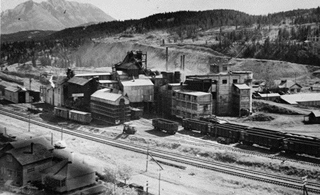

A view of the booming International Coal and Coke Company Ltd. at Coleman, ca. 1945; increased demand for steam coal during the war years led to greater production within the industry.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NC-54-2930

-

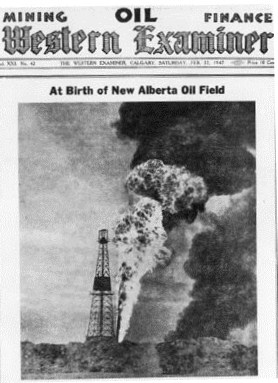

The discovery of a major oil deposit at Leduc, Alberta, foreshadows a decline in the province’s coal production.

During the decade after the 1947 discovery, many mines close and most coal towns decline significantly. On February 22, 1947, an issue of The Western Examiner proclaims the discovery of the Imperial Leduc #1 oil well as the birth of a new Alberta oil field.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-789-80

-

Large-scale surface mining begins in Alberta near Lake Wabamun to fuel a large thermal electric power plant.

A heavy-duty truck hauling coal at the Wabamun surface mining operation near the TransAlta Power Plant demonstrates the advanced mechanization propelling Alberta’s modernizing coal industry in the 1960s.

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, gr1989.0516.1088#1

-

The last mine in Edmonton’s river valley closes.

The Whitemud Creek Mine in Edmonton’s river valley in 1968; this operation is the last of Edmonton’s coal mines to close in 1970. At this time, the mine continues to rely on horses to haul coal to its opening.

Source: City of Edmonton Archives, EA-20-4998

-

Drumheller Valley and Canmore mines close after decades in operation.

The Atlas Mine in Drumheller Valley stops production in 1979 and officially closes in 1984. The large structure is the last wooden tipple standing in Canada. The mine is a Provincial Historic Resource, a National Historic Site and one of the region’s star attractions.

Source: Courtesy of Sue Sabrowski and the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology

-

Mining near Forestburg ends after more than seventy years.

The retired Marion 360 Stripping Shovel at the Diplomat Mine site near Forestburg, Alberta; the interpretive site is a Provincial Historic Resource and Canada’s only surface coalmining museum. The kind of large-scale surface mining conducted near Forestburg requires massive equipment such as the Marion 360.

Source: Diplomat Mine Interpretive Site

-

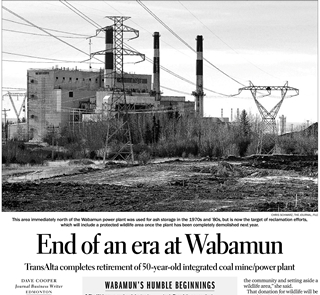

Wabamun coal-fired power plant is retired and demolished after almost fifty years in operation.

The Wabamun power plant in the final stages before destruction it begins generating electricity in 1962 by burning coal mined at large-scale surface operations near Wabamun Lake. The planned closure of the plant is featured in an Edmonton Journal article on April 2, 2010.

Source: Edmonton Journal