-

Clovis phase spear points used in present-day Alberta.

Clovis phase spear points represent the oldest hunting technology in Alberta, and indeed all of North America. These fluted, jagged stone points would be attached to a bone or wooden shaft and used to hunt enormous prey such as mammoths and mastodons.

Source: Historical Resources Management Branch, Archaeological Survey

-

Atlatl (spear-thrower) technology emerges in present-day Alberta.

Atlatls were used by early hunter’s to increase the velocity of their projectile weapons. Spears or darts thrown with an atlatl could deliver devastating wounds to an animal, allowing the hunter to kill the animal from a safe distance.

Source: Courtesy of Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump

-

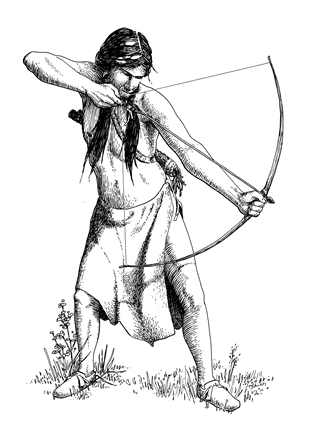

Bow and arrow technology reaches present-day Alberta.

Bow and arrow technology in North America appears to have developed first in the Arctic before spreading south throughout the continent. The bow and arrow was ideally suited for use in the wide open spaces of the Great Plains, and was widely adopted across the region.

Source: Courtesy of Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump

-

The ‘Horse Revolution’ begins in present-day Alberta.

Horses were brought to North America by Spanish colonists in the sixteenth century. From the Spanish colony of New Mexico, horses spread across North America, reaching present-day Alberta in the 1730s. The adoption of the horse had a significant impact on the hunting/transportation patterns of Plains First Nations peoples.

Source: Royal Alberta Museum

-

Rocky Mountains National Park is established by the Canadian government.

One of the main attractions of the new park was the site’s natural hot springs. The luxurious Banff Springs Hotel, built by the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1888, pumped water from the hot springs into its swimming pools and treatment rooms. Tourists flocked to the site to take advantage of the water’s supposed therapeutic healing powers.

Source: Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, v263-na-3562

-

The Calgary Water Power Company opens Alberta’s first hydroelectric plant.

The company was owned by entrepreneur Peter Prince, who also ran the Eau Claire & Bow River Lumber Company. From 1894 to 1905, the company was the major electricity provider for the city of Calgary.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-4477-44

-

The City of Edmonton purchases the Edmonton Electric Lighting Company.

The decision in favour of public ownership was made after repeated disruptions in service from the privately-owned utility. Edmonton was the first major urban centre in Canada to own its own electricity utility.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NC-6-271

-

The Calgary Power Company is formed.

The founder of the company, Max Aitken, was initially drawn to the region by its vast hydroelectricity potential. The company would develop into Canada’s largest investor-owned utility. In 1981, the company changed its name to TransAlta Utilities Corporation, in order to better reflect its provincial reach.

Source: Photo courtesy of TransAlta

-

Alberta’s First hydroelectric dam opens at Horseshoe Falls.

Owned and operated by Calgary Power, the Horseshoe Falls Dam was the first of two such facilities built on the Bow River system prior to the First World War. A second hydroelectric dam began operations at Kananaskis Falls in 1913.

Source: Glenbow Archives NA-3544-28

-

The Ghost Hydroelectric Dam begins operations

This massive facility was the largest hydroelectric dam in Alberta at the time it was built. The Ghost Power Plant more than doubled the amount of electricity generated by Calgary Power, which was already the province’s main energy supplier.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-5663-44

-

The first Rural Electrification Association (REA) in Alberta is established in Springbank.

Over the next two decades, a total of 416 REAs would be established across the province. These organizations would play a crucial role in the spread of electricity to rural Alberta.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-4160-20

-

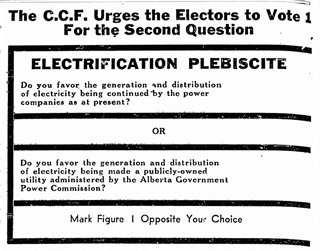

Voters of Alberta narrowly reject proposal for public ownership of electricity utilities.

The 1948 provincial election included a plebiscite concerning ownership of electricity utilities in Alberta. Rural areas largely voted in favour of public ownership, while urban voters (particularly in southern Alberta) supported a continuation of private ownership. In the end, the vote was extremely close, with public ownership defeated by a mere 151 votes.

Source: Image courtesy of Peel’ Prairie Provinces, a digital initiative of the University of Alberta Libraries

-

Cowley Ridge Wind Farm begins operations near Pincher Creek.

Cowley Ridge was Canada’s first commercial wind farm. A total of fifty-two wind turbines were installed in 1993-94. In 2000, the project was expanded with the addition of fifteen new (and much more powerful) turbines.

Source: Photo courtesy of TransAlta

-

Drake Landing Solar Community opens near Okotoks, Alberta.

Drake Landing is North American’s first fully integrated solar community. This award-winning initiative uses solar heating technology to provide the community with the majority of its space heating and hot water needs.

Source: Wikimedia Commons/CA-BY-SA-3.0

-

The City of Edmonton announces the launch of the ‘waste-to-biofuels’ project.

The waste-to-biofuels project will convert garbage into biofuel by harvesting carbon from the waste material. The project includes an Advanced Energy Research Facility, which opened in 2012.

Source: Photo Courtesy of Enerkem